TIMELINE

The Saxons

There may have been a wooden church

on the site from c700

We

can assume that the causeway and ferry crossing continued into Saxon times

and no doubt this encouraged the growth of a Saxon settlement by the eastern

landing point Shoreham takes its name from the Saxon ‘ham’ meaning the

home or dwelling place near the shore. Other Saxon settlements soon began

to appear in the Adur Valley, most doubtless on the sites of earlier

villages. In addition to establishing themselves on the old hill-forts on

the high points of the Downs they settled at and named many places in the

neighbourhood and elsewhere. The Saxon endings of “ham”, “ing” and “ton”,

common in the Adur Valley, indicate where Saxon communities lived.

From earliest times small boats would have plied back and forth along

the Adur loaded with cargo. Downstream went raw materials such as Horsham

slabs for roofing, but the most important in any period would have been the

timber from the Wealden forests to provide wood for houses, shipbuilding,

tools and fencing on the relatively treeless Downs and coastal pain. At

certain periods in history other raw materials such as iron ore, clay and

charcoal were ferried downstream. Upstream the boatmen laboured to bring

grain, flour and other foodstuffs to feed both the farmers of the poor

Wealden soils and the craftsmen who laboured there. As knowledge of

farming methods improved such cargoes began to include manure and lime

(burnt chalk) to be spread on the clay soils of the Weald to improve their

fertility. As with all rivers, the Adur needed a port where the boatmen

could transfer goods from the smaller craft used on the river to the larger,

sea-going vessels. By Saxon times, at least, this port was at Steyning,

where routes were focused on the border between the high Downs and low

Weald. Inevitably people made their homes here and a market was

established, so that by late Saxon times a sizeable town, with its own

mint, had grown up.

The origins of Christianity in this country are hazy. However, we

know from the writings of Bede, an eighth-century Northumbrian monk, that a

successful mission had been sent from Pope Gregory in Rome to Kent under

Augustine in 597. We are equally hazy about the origins of the first

churches, but it seems probable that Christianity developed at different

rates in different parts of the country.

St Wilfrid, the exiled Bishop of York, brought Christianity to Sussex in

681. He was granted land by King Aethelwealh to build a cathedral at

Selsey. Shortly afterwards Caedwalla of Wessex conquered the little

kingdom of the South Saxons, but allowed Wilfrid to continue his work, and

himself became a Christian. With the spread of Christianity through all

the South Saxon kingdom came the building of churches. These, of course,

were at first of wood, but as the centuries passed they were replaced by

more substantial buildings in stone. As well as in the church of St

Nicolas, Old Shoreham, the work of Saxon masons may still be seen at many

places in Sussex, and nearby too – St Botolphs, further up the Adur, and at

Sompting.

Perhaps as early as 850, but certainly before

900, the Saxons built the present church in Old Shoreham. The traces are

slight but the evidence of the Saxon foundation is clear if you know where

to look. The boundary wall on the south side displays the curved shape

characteristic of a Saxon churchyard and the nave of the church retains some

clues to its origins.

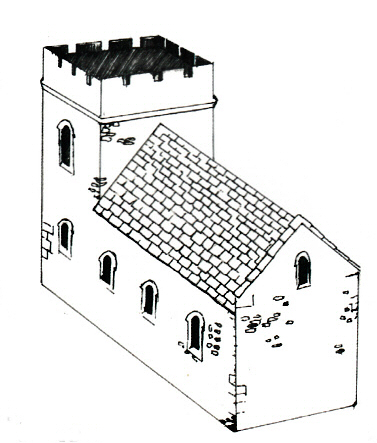

The first stone-built church of St Nicolas now forms the western end of the

present structure. The church would have consisted of a nave and chancel

only, with squared rubble walls, small square or round headed windows high

up, and a narrow and tall rounded chancel arch. A tower at the west end

came later and there are traces, on the north side, of the Saxon doorway

which led into it.

Doorways and windows would have been narrow and bridged on top with a flat

stone. On the outside Saxon masonry is very distinctive. One of its best

known features is long and short work at the corner of the building. The

simple long and short work – large vertical stone slabs set alternately with

horizontal slabs - roughly put together is seen in the column marking the

change of line in the middle of the exterior of the north nave wall. This

and the very simply constructed closed-up door arch a metre or so to the

west of it are clearly of very ancient Saxon origin. The arch led to the

base of the tower in the old Saxon church. The size and shape of this tower

at the west end although long demolished can be seen on the plan and traced

in the present building. There are in addition two blocked-up Norman

doorways, one on each side of the nave.

The ground plan suggests that the Saxon worshippers would have gathered

around their priest standing at the junction of nave and chancel. It is

likely that many late Saxon services still tended to follow the Celtic

tradition (as opposed to the Roman) with services in Old English and

participation by all, but this was to change with the coming of the Normans.

It is a good idea to stand back and view the building as a whole from the

outside. By standing back and just looking you will probably be able to

see quite plainly where the church has been extended in length and possibly

also in width and height over the centuries. This will help you with your

exploration once you get inside.

Stone church built

c850-900

Saxon stonework visible on the north side